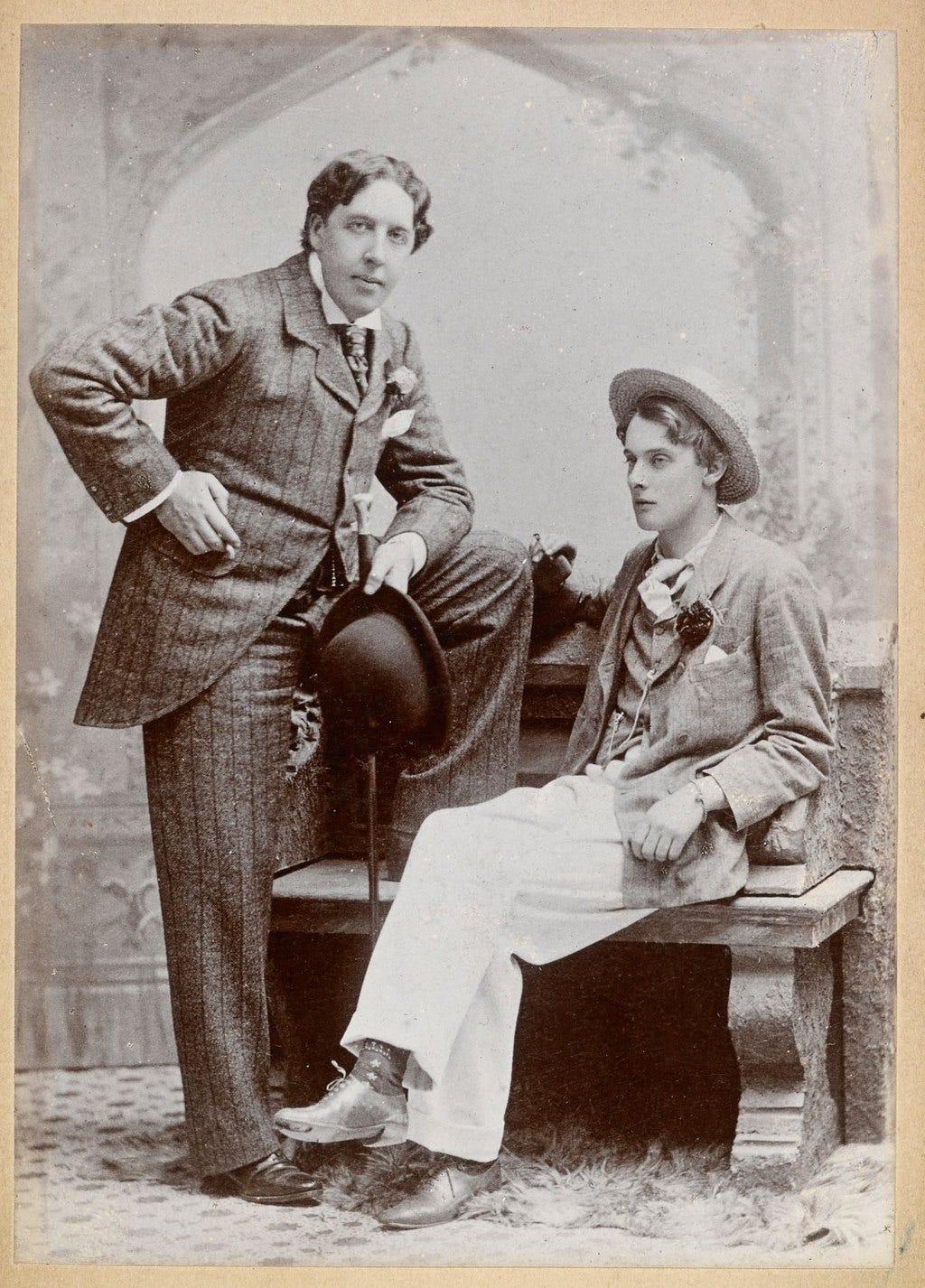

Above: Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas in 1893.

[Author’s note: I wrote the following essay just for fun in 2017. I recently re-wrote the whole thing, and now present it here for anyone of interest.]

“It is a remarkable thing that while Oscar Wilde’s life was immoral, his art was always moral.” So said Wilde’s companion, Lord Alfred Douglas. That statement is certainly true of Wilde's only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. The book is captivating not only for its elegance of style and dramatic force, but because of Wilde’s haunting depiction of the moral life.

The novel tells the story of a beautiful young man named Dorian Gray. One day, he wishes that he might remain young forever while a portrait of him—freshly painted—would age in his place. His wish is mysteriously granted. Dorian then finds that he is exempt—or so he thinks—from bearing the burdens of old age and the consequences of his actions.

He is soon corrupted by the seductive words of a hedonist, Lord Henry Wotton. Dorian's innocence curdles into vice. Each immoral act leaves its mark—not on his face, but on the painting, which grows hideous and grotesque. Dorian both loves and hates the painting. He spirals into a life of cruelty and indulgence, including the murder of a friend.

Dorian, it turns out, is not exempt. The toll of his actions is real, though hidden from view. As the illusion of invincibility wanes, he becomes aware of the dark reality: the ugliness of his character is transferred to the picture. His outer beauty veils a ruined soul. No one else sees it—but he does. In time, the picture cease to fascinate; it torments him, and he comes to regret it:

Why had he kept it so long? Once it had given him pleasure to watch it changing and growing old. Of late he had felt no such pleasure. It had kept him awake at night. When he had been away, he had been filled with terror lest other eyes should look upon it. It had brought melancholy across his passions. Its mere memory had marred many moments of joy… It had been like conscience to him. Yes, it had been conscience.

Dorian struggles to admit the obvious: the painting does not accuse him falsely. At one point we read that his “own soul was looking out at him from the canvas and calling him to judgment.” In that sense, the painting is the moral law, a private indictment—ignored at our own peril, never erased. In a final act of madness, Dorian stabs the picture—and kills himself.

In the end, he is the victim of his own depravity. His death enacts what Saint Augustine called incurvatus in se—the soul habitually turning inward and finally caving in upon itself.. Sin consumes the soul the way cancer consumes the body: often quietly, until it is too late.

What are we to learn about the moral life from The Picture of Dorian Gray? The following points come to mind.

1. C. S. Lewis once said that good and evil

both increase at compound interest. That is why the little decisions you and I make every day are of such infinite importance.1

Each of us, little by little, travels toward either a heaven or a hell, and more often than not we are unaware of the road’s direction until the end is near. That is why we need other people—even books—to show us what we cannot see in ourselves. We need confession, prayer, and a steady vision of the good life, because self-deception blinds us to our own decline. What seem like small moral choices—“It was just a little lie,” or “No one’s getting hurt”—can form habits that lead us to ruin. Evil rarely looks like evil at the start.

Oscar Wilde understood this. In De Profundis, a letter he wrote to Douglas from prison, he said:

The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease... Tired of being on the heights I deliberately went to the depths in search for new sensation. What the paradox was to me in the sphere of thought, perversity became to me in the sphere of passion. I grew careless of the lives of others. I took pleasure where it pleased me, and passed on. I forgot that every little action of the common day makes or unmakes character, and that therefore what one has done in the secret chamber, one has some day to cry aloud from the house-top. I ceased to be lord over myself. I was no longer the captain of my soul, and did not know it. I allowed pleasure to dominate me. I ended in horrible disgrace.2

In Wilde’s poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, he puts the warning in verse:

“Oho!" they cried, "the world is wide,

But fettered limbs go lame!

And once, or twice, to throw the dice

Is a gentlemanly game,

But he does not win who plays with Sin

In the Secret House of Shame.

For Dorian, that warning comes too late.

2. Unlike the rest of us, Dorian is given a rare gift: the ability to see his own moral decay as it happens. The painting becomes a mirror of his soul. We are not so fortunate. Lacking such privileged access, we must ask what “paintings” we might place in our own lives—what guardrails, disciplines, or voices of truth—to help us see ourselves as we are. The portrait should have rescued Dorian from illusion. But it does not.

3. Why it does not is one of the book’s central ironies—and one of life’s. Humans are gifted at twisting reality to fit themselves, rather than reshaping themselves to fit reality. From the moment Dorian makes his wish, he begins denying the truth about who he is and what he is becoming.

Denial of reality is thus a large theme in the book. When Sibyl Vane, the young woman he once loved, takes her life, Dorian is wracked with guilt—at first. But Lord Henry reframes the tragedy. In an eery speech, he persuades Dorian to see her suicide not as a consequence of his cruelty but as a poetic flourish in the story of his own life. Sibyl’s suicide, he says, was a rare act performed for Dorian himself.

“No, she will never come to life. She has played her last part. But you must think of that lonely death in the tawdry dressing-room simply as a strange lurid fragment from some Jacobean tragedy, as a wonderful scene from Webster, or Ford, or Cyril Tourneur. The girl never really lived, and so she has never really died. To you at least she was always a dream, a phantom that flitted through Shakespeare's plays and left them lovelier for its presence, a reed through which Shakespeare's music sounded richer and more full of joy. The moment she touched actual life, she marred it, and it marred her, and so she passed away. Mourn for Ophelia, if you like. Put ashes on your head because Cordelia was strangled. Cry out against Heaven because the daughter of Brabantio died. But don't waste your tears over Sibyl Vane. She was less real than they are.”

And later:

“In the present case, what is it that has really happened? Some one had killed herself for love of you. I wish that I had ever had such an experience. It would have made me in love with love for the rest of my life... One should absorb the colour of life, but one should never remember its details. Details are always vulgar.”

Dorian believes Lord Henry, which is easier than facing the bitter truth. He tells himself:

“Poor Sibyl! What a romance it had all been! She had often mimicked death on the stage. Then Death himself had touched her and taken her with him. How had she played that dreadful last scene? Had she cursed him, as she died? No; she had died for love of him, and love would always be a sacrament to him now. She had atoned for everything by the sacrifice she had made of her life. He would not think any more of what she had made him go through, on that horrible night at the theatre. When he thought of her, it would be as a wonderful tragic figure sent on to the world's stage to show the supreme reality of love. A wonderful tragic figure? Tears came to his eyes as he remembered her childlike look, and winsome fanciful ways, and shy tremulous grace. He brushed them away hastily and looked again at the picture.”

This is similar to what J. Budziszewski has called the revenge of conscience. Coping with his own moral decay requires this twisting of reality; it is what gives his hedonism any semblance of plausibility or appeal.

4. One of Lord Henry’s mistakes is to think of freedom as the ability to do what I want, rather than the power to do what I ought. Freedom presupposes that there is an ought, and that I am free only insofar as I am able to obey it. The addict can get the drug he craves, but he isn’t free. Freedom lies not in license to indulge—even the slave can do that—but in the power to show restraint and the ability to do what I should, even if I don’t want to do it. Chesterton put it like this:

And the more I considered Christianity, the more I found that while it had established a rule and order, the chief aim of that order was to give room for good things to run wild.

This is the paradox: proper rule, not moral license, sets us free. Dorian wishes to liberate himself from the shackles of obligation. But, on the contrary, learning to fulfill obligation is a condition for his freedom.

5. Wilde further shows that moral reality buries its undertakers. It is built into the grain of the world. You can ignore it, defer it, twist it—but not eliminate it. Each new “liberation” in Dorian’s life is another length in the noose around his neck. Eventually, the reckoning comes.

6. The story of Dorian Gray runs counter to our myths about right and wrong. We tend to think that actions are harmless unless someone is obviously hurt. But this is a comforting fiction, not a serious moral insight. We are cushioned by wealth and distraction from the initial consequences of our vices, which means we can easily rationalize them to ourselves when nobody is immediately or obviously hurt. But hurts are not always immediate or obvious, and it takes more than our private judgment to tell. A harm can be more subtle than physical pain. So we tell ourselves that nothing is wrong. But reality has a way of reasserting itself. As Aquinas observed, a small mistake in the beginning becomes a big one in the end. The consequences may not come at once, but they come. Moral habits form slowly—often imperceptibly. The passions do not shackle us overnight, but they do shackle us. A small lie seems harmless—until we become liars. A little selfishness feels private—until it hollows out the capacity for love. Litter seems trivial—until the trash is piled so high that it can no longer be ignored.

Douglas, like Wilde, was a late convert to Catholicism. Both men, radical in art and lifestyle, were ultimately driven back to moral reality after lives of “senseless and sensual ease.” The damage wrought by indulgence was not enough to silence their consciences. That is both an encouragement and a warning.

Ultimately, we see in Wilde’s art more honesty than he showed in most of his life—and many stern but redemptive reminders: the inner life matters, conscience endures, and the moral law cannot be rewritten by wit.

Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book 3, “Christian Behaviour,” chap. 9, “Charity” (New York: HarperOne, 2001), 132.

The phrase de profundis comes from Psalm 130: “out of the depths I cry...”.