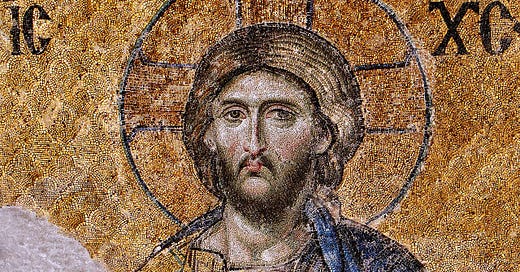

Above: Jesus Christ Pantocrator, from the Deisis mosaic in Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

The following exchanges, published in multiple parts, are drawn from a real email correspondence between me and a young woman named Mary, which began in August 2024 and continued into 2025. The text has been lightly edited for clarity and flow, with the original meaning preserved but the text improved for readability in a challenge-response format, where the challenge takes the shape of a question or statement.

By God’s grace, Mary recently reunited with the Catholic Church. I include our letters back and forth because she raised good questions that many inquirers are asking today. As you can see, she’s sharp, honest, and a genuine seeker of the truth.

Note: the exchanges below are repeated in chronological order and they get more detailed as they go along. Also, for context, it’s important to know that most of her concerns come from objections to Catholicism that one will find from recent Eastern Orthodox apologists on Youtube and Twitter.

Mary:

I was born into a Catholic family, but the Catholicism I knew growing up always felt more cultural than spiritual. No one really asked questions. Once we completed the sacraments and checked the boxes—baptism, confirmation, catechism classes—that was the end of it. People went along with what they were taught, but no one seemed deeply engaged.

My own questions started when I was about ten, mainly because of my dad, who’s Protestant. He was the one who first introduced me to the idea of “a personal relationship with Jesus,” as Protestants often say. That idea resonated with me, and over time I found myself leaning more and more in that direction. By the time I was a teenager, I had become, in effect, a “secret Protestant.”

When I was seventeen, I made that internal shift public by deciding to get baptized. My Catholic family didn’t take it well. But when I explained my reasons—mainly the usual objections about Mary and the saints—no one could give me a clear response. I wasn’t trying to rebel; I just had questions no one seemed prepared to answer.

Even so, I didn’t have a Protestant church I could attend. So for the next several years, I was essentially without a church. That remained the case until recently. I started attending a local church earlier this year (2024). I had been praying for God to lead me to a “biblical” church, the kind I had always hoped to find. About four months in, I met a young man who was a serious Catholic. He surprised me—not only because he had answers to the questions I’d carried for years, but because he didn’t seem to question his faith at all. That was new to me.

He encouraged me to do the work myself: to dig, to read, to compare. So I did. I started reading deeply, especially on the historical side of things, because I felt that history might offer a more objective path. The more I read, the more convinced I became that Protestantism wasn’t the answer—historically, practically, or even biblically. But I still found myself caught between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

It seemed clear to me that the real issue was authority. So I focused on the Papacy, again trying to approach it through the lens of history. But history, I quickly discovered, is messy. Both Catholics and Orthodox present strong historical cases, with their own citations, canons, councils, and quotes. At one point, I remember thinking: they can’t both be right, but they both sound so confident.

That’s when I started looking for Catholic responses to Orthodox objections—and that’s how I found your writings at Controversiam.

Thank you for your willingness to help me as I work through my discernment of Catholicism. I truly appreciate it. Somehow, I’ve found myself drawn into the world of apologetics, and to be honest, while I no longer find Protestantism convincing, I'm trying to make sense of it all but have encountered many questions and objections related to Catholicism, which has made the process more difficult.

My current predicament is this: I am kind of stuck between Catholicism and Orthodoxy. And because the issue of authority seems to be the one thing I need to answer, I have focused on the Papacy through history.

Wesley:

I agree that the Papacy is a good place to start. However, it’s important to understand that Eastern Orthodoxy (EO), which is not a monolith but a collection of distinct traditions, is not necessarily true just because the Catholic view of the Papacy is false. Both could be wrong. Choosing EO simply because you reject Catholicism would be a mistake. Much of the EO content online consists of critiques of Catholicism, but this doesn't necessarily validate their own positions or traditions. EO isn’t popular enough to attract the same level of critical scrutiny that Catholicism faces from Protestants, Orthodox, and others.

The inconsistencies within EO on issues like divorce and remarriage, contraception, baptism, and the nature of sacraments in general are strong reasons to reject it. Additionally, the fact that EO accepted the filioque and the Papacy at the Council of Florence (before their people rejected it and pressured their bishops to do the same) delivers another decisive blow to EO. (I highly recommend Fr. Thomas Crean’s latest book on the filioque and the Council of Florence). And all this is before even considering the Papacy itself.

Mary:

I’ve come across Catholics and historians who admit that the East was not fully aligned with the Papal claims—claims such as the Pope being the successor of Peter or Peter being the rock. It seems more accurate to say the East acquiesced to these claims rather than fully embraced them.

Wesley:

First, what do you mean by “the East”? Intentionally or not, people will use that phrase vaguely and generally to gloss over difficulties, such as the Fathers or Saints who affirmed Papal prerogatives. History is indeed messy, which is why vague, general statements about “the East” versus the Papacy generate more heat than light.

Second, my sense is that the “we only acquiesced” view is quite popular and perhaps it must be relied upon to explain away the important historical evidence for the Papacy. But I think it is a very strange reply to make. If I'm an EO, why would it be a good thing if “my guys” routinely, over the course of centuries, acquiesced to rank heresy on the biggest stages and on the most important topics—especially if the guys they're acquiescing to (Celestine, Leo, Gregory, etc) are Saints in my own tradition?

Mary:

If the East never fully or unanimously accepted the papal claims, how can we be sure that the Papacy—understood as a divinely instituted office—is truly part of the deposit of faith?

Wesley:

Try to ask your question in relation to another dogma that isn't under contention right now. For example, “if the numerous Arians never really unanimously accepted the Trinitarian claims, how do we truly know the Trinity is in the deposit of faith?” Well, you would need to know whether or not the authority that declared the Trinity to be a dogma was the Church Christ founded. And on the Catholic view, the Church is a divinely instituted society with a Spiritual Head, who is Christ, and a visible Head who is the Bishop of Rome. To find that Church, you have to follow the apostolic teaching backwards.

If you begin with Vatican I and trace the succession backward, then—unless there is a break—that is the Church. This is the approach Irenaeus takes in Against Heresies III.

Here's another thought. Vatican I clearly defined the Papal prerogatives. But there is no clearly defined EO ecclesiology. Ask different EO scholars, and you'll get different answers, each centered on a vague notion of “conciliatory” or “collegial” rule of bishops. But let's pretend there is a singular clear position and ask the same question: “if the West never really unanimously accepted the EO ecclesial claims, how do we truly know those claims (as something divinely instituted) is in the deposit of faith?”

Which question has a more probably reply? Why ask it of the Catholics but not anyone else? I'm not saying you haven't asked it, but typically Catholicism gets attacked by all sides because it's bigger, and people forget to subject the other sides to the same level of scrutiny.

Finally, why would it matter if some people, even in “the East”, merely acquiesced or even rejected a claim? The entire Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches did not acquiesce to Chalcedon—they rejected it and have been separated ever since. Does that somehow cast doubt about Chalcedon's decrees? Should we abandon EO and Catholicism simply because some groups didn't accept it? What if those groups merely acquiesced at Chalcedon and later departed?

Mary:

There is also the issue of immediate universal jurisdiction. From what I can see in history, when the Pope tried to intervene directly without the East asking him to, they kind of rejected what he was trying to do—at least sometimes, according to what some EO’s claim, which makes things very confusing.

Wesley:

A few thoughts, which we can unpack more fully later. First, I don’t think it’s accurate to say that “when the Pope tried to intervene directly without the East asking him to, they kind of rejected what he was trying to do.” That is too broad a generalization. Even if it were true, I’m not sure why it would matter in the way you're suggesting. After all, large parts of the Church rejected the Council of Chalcedon and have been separated ever since. Should we then conclude that Chalcedon lacked authority? My five-year-old daughter sometimes rejects my authority, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have it.

Second, the concept of “universal immediate jurisdiction” wasn’t formally defined at that time, so we shouldn’t expect to find people explicitly affirming or denying a proposition that hadn’t yet been articulated. It's similar to the Trinity: the full Nicene formulation wasn’t defined until the fourth century, but that doesn’t mean the underlying reality wasn’t already believed, at least implicitly.

So rather than asking whether the East accepted a later definition in earlier centuries, the better question is whether the essential idea—or something that entails it—was present and not rejected. That’s the sort of continuity we should be looking for.

Mary:

The Orthodox argue that the East never accepted the idea that the Pope had universal immediate jurisdiction. Instead, they say the Eastern Churches governed their own affairs and only appealed to Rome when needed—based on provisions like the Sardica canons. In that view, the Pope functioned more as an arbiter than someone with supreme authority over the whole Church. How do we reconcile that historical picture with the way the Papacy functions today?

Wesley:

I think that's a bad misunderstanding of Sardica: how it came about and why it functioned the way it did. We can discuss that in more detail later, and of course I'll be addressing some of these issues as I work through Whelton's book. But I’m not aware of anything like persuasive evidence showing that the Pope was seen only as an arbiter. And of course I think we have a lot of evidence to the contrary.

It’s hard to know where to start at this high level of generality, but I’m happy to dig deeper wherever you'd like.

Mary:

Another issue is the idea of primacy in the sense that “we need the Pope’s approval for something to be accepted by the whole Church”—which is how Catholicism understands it today. But the Orthodox would say that, historically, it was the ecumenical councils that held the highest authority.

Wesley:

For those interested in further study, I’d suggest starting with the Catholic Encyclopedia article on General Councils. Next, Fr. Crean’s book on the Council of Florence and the filioque is an excellent follow-up for those who wish to explore more deeply the nature and authority of councils.

In my view, the evidence strongly indicates that the Pope has historically played the decisive role in determining which councils are authoritative. The actions of Rome and appeals to Rome—for convoking, confirming, ratifying, or at times annulling councils and their canons—are ubiquitous in the historical record. Nothing even remotely close can be said of the other patriarchates. The case of Pope Vigilius and the canons of Justinian, though complex, illustrates the point rather than undercutting it.

No Catholic denies the supreme authority of Councils. But they were supremely authoritative insofar as the Head, the Bishop of Rome, confirmed or accepted them.

Mary:

When bishops and emperors sought Rome’s approval for councils and canons, it was primarily because they wanted consensus among all the five Patriarchs, and the Pope, as Patriarch of the West, was part of that picture. In that sense, couldn’t we say the unique claims of the Papacy are not supported by the historical record?

Wesley:

The idea of a “Pentarchy”—five Patriarchs—doesn’t really surface until Justinian, which is already quite late. Moreover, two of those sees—Jerusalem and Constantinople—didn’t even exist as patriarchates until Chalcedon. So if one insists on a Pentarchic model as the necessary criterion for ecumenicity, one would have to reject not only the first four councils but all of them. Chalcedon itself, for instance, confirmed the status of those other sees while only three were represented. But if five were required, then Chalcedon lacked authority, which would in turn undermine the very basis for recognizing five Patriarchs in the first place. It's a self-defeating principle.

You might ask: however many Patriarchates there were at a given time, did not all the existing ones have to agree, which explains the appeals to Rome? That explanation doesn’t square with the historical data. If you examine how emperors, council fathers, and others treat the Bishop of Rome—how they sought his confirmation, or appealed to him to nullify decisions—it becomes clear that his role was understood as qualitatively distinct from the others. Even the Justinian canons illustrate the point. No one else was treated in comparable terms.

Moreover, at least one early council—Ephesus in 431 AD—lacked full patriarchal agreement. John of Antioch rejected it, convening his own robber synod! Although he reconciled years later, that didn’t retroactively make the council ecumenical. It was already recognized as such prior to his assent. So here we have a concrete example: not all existing Patriarchs agreed, and yet the council was authoritative. Why? Because of the Bishop of Rome.

As for the Papacy itself, here’s how I came to see the matter. I think any fair-minded Eastern Orthodox believer would acknowledge that the New Testament attributes a distinct role to Peter. In Matthew 16:18–19, Jesus gives the keys of the kingdom and the title rock of the Church to him alone. In Luke 22:31–34, he is uniquely charged with strengthening the brethren. In John 21:15–17, he is commissioned to shepherd the universal flock. These aren’t trivial details. Christ seems to confer a singular kind of pastoral and doctrinal responsibility on Peter—one that goes beyond symbolic primacy.

Christ clearly assigned some kind of prerogative to Peter, and it wasn't something that died with Peter but rather persisted on in the Church through apostolic succession. Moreover, as a preliminary philosophical conviction, it seems that there had to be a visible head and unity of the universal Church, which is the Body of Christ; and that the prerogatives of that head had to be the same or similar to any that the Eastern Orthodox already applied to the Church as a whole, however they define it. Indeed, it seemed to me that the Church must possess them through (or in union with) the head.

Now, for me, I asked which of Catholicism or EO fit better with that philosophical conviction and the historical data? I thought it was Catholicism.

… Continue to Part 2.

Thanks for answering all my questions with care and dedication, Wesley! I hope our conversation can help those who are looking for answers! :)